Friday, March 03, 2006

Synchronous

(If you haven't read the introduction, please read it first.)

A Science-Fiction Short Story

By The Person Who Posts as Doctor Bean

2006

By The Person Who Posts as Doctor Bean

2006

Dalp stumbled from the dark bedroom to the sunny kitchen, rubbing the sleep from his eyes. His wife and daughter were already at the table. They smiled at him as he entered. He kissed his wife’s forehead, tousled his girl’s hair, and then sat and started eating. He had a lot of work ahead of him. He didn't know it, but he was on the brink of the greatest discovery his people had ever made.

“Sweetness,” his wife said “Gat had another perfect score on her science test!”

“That’s great, Gat!” Dalp beamed.

Gat was only ten stars old, but she was already a terrific science student. Dalp was proud of how smart she was. As he stared at her over his meal he was reminded how much like her mother she looked. Her mother was proud too. She knew that Gat wanted to be a great science student just because she wanted to be an engineer, like her father, but that seemed as good a reason as any.

Their kitchen was well lit by the low sun through a large rectangular window in the ceiling positioned to illuminate the center of the room where the table was. On the edges of the window a lattice pattern was painted to allow a little less light through and leave the perimeter of the room in partial shade. They had lived in their house for many stars, and the sun had already bleached the lattice pattern into the wood floor of their kitchen, since of course, light and shadow never moved unless a cloud blew overhead.

“Do you want to show me what you’re studying now?” Dalp asked.

“Let her finish eating” his wife protested, but Gat had already run off and returned with her science textbook, Our Beautiful World. She opened it on the table and pointed to a page.

“We’re learning about the World map,” she bragged.

“Oh. The World map is very important. It helps you understand our weather and…”

“And where our water comes from,” Gat interrupted.

“Right. Tell me what you’ve learned about the World map.” Dalp said between bites of food.

“Well, World is round. It’s shaped like a giant ball.”

“That’s right.”

“And the spot that’s right under the sun is called sunpoint. So if you were standing there the sun would be right over your head and your shadow would be right under your feet.”

“But can you stand there, Gat?”

“No. It’s too hot. No one’s ever been there, or even close to it.”

“That’s right. What else?”

“There’s an opposite point on World called darkpoint. That’s harder to figure out, because on the dark side of World you don’t have your shadow to use to figure out where you are, so you have to use math and the stars, but darkpoint is the point exactly opposite sunpoint. So if you were standing there, the sun would be straight down past your feet and then through all of World and on the other side.”

This is the definition of “star” in the glossary of Our Beautiful World:

star

1. A giant ball of fire that creates heat and light. On the dark side these look like bright dots in the sky. Our sun is just another star, but is much closer, so it looks bigger in the sky.“Very good. And can you stand at darkpoint, Gat?”

2. A unit of time equal to the amount of time it takes World to rotate around the sun. This unit was first called “star” before we knew that World rotates around the sun, since this is the amount of time it takes the stars to appear to rotate around World.

“No. Nobody’s been close to it either. It’s too cold. Everything’s frozen there.”

“Right. And between the bright side of World and the dark side of World there’s a circle where the two halves meet. What’s the name of that circle?”

“It’s called the Ring, and it’s where all the living things are on World.”

“That’s right, all of the people and animals and plants live on the Ring between the two halves. Why aren’t there living things anywhere else on World?”

“Because the Ring is the only place that’s not too cold or too hot, and it’s the only place there’s water.”

“That’s very close. It’s the only place there’s liquid water. Do you know what that means?”

“Yes. Water that flows, like in rivers and lakes, so animals can drink it. If water flows out of the Ring into the dark side, it freezes, and on the bright side it gets too hot and… um…”

“Evaporates.”

“Right. It makes clouds.”

“Right.”

While he quizzed her, Dalp peeked at the open pages of her text.

Map Coordinates

The map of World is divided up by two sets of imaginary circles that allow map makers to give every point on World its own unique pair of numbers that can tell anyone where that point is. These numbers are called coordinates. The two coordinates are called sunangle and ringangle.

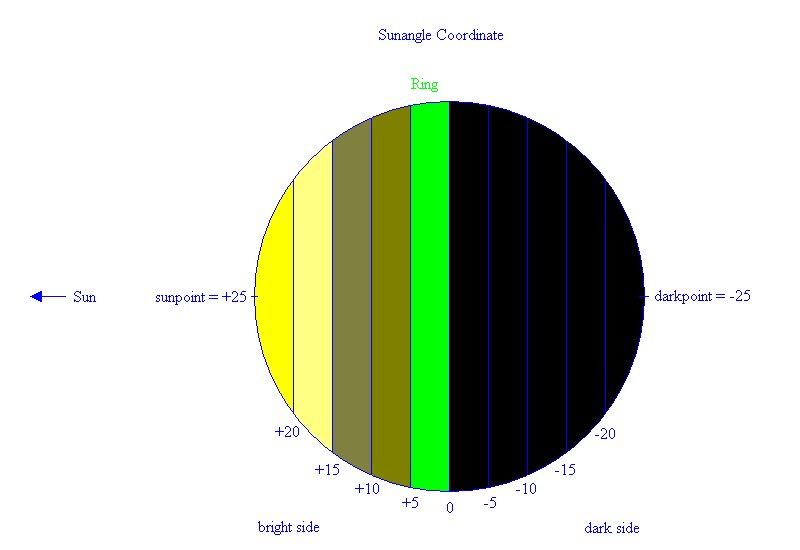

Sunangle Coordinate

On the bright side, sunangle is simply the angle of the sun above the horizon. At sunangle zero the center of the sun is on the horizon. At sunangle +5 arcs, the sun is 5 arcs above the horizon. So at sunangle +25 arcs, the sun is straight up, which happens at sunpoint. The sunangle coordinate is defined the same way for the dark side except that the sun is not visible. The coordinate on the dark side is a negative number and is the angle of the sun below the horizon.

All living things on World live between sunangle of 0 and +5 arcs, and this is also where most of the liquid water exists. This haven for life on our otherwise inhospitable World is called the Ring.

Dalp thought this was pretty accurate for an elementary school text. The Ring was simply the geographic distribution of World’s biosphere. It actually extended from about -1 arc to +7 arcs, and people had explored somewhat further, but the principles in the book were correct.

The glossary of Our Beautiful World defines “arc”:

arc

A unit of angle measure that divides the circle into 100 equal parts. A complete circle is therefore 100 arcs and a right angle is 25 arcs.“Dalp,” his wife interrupted his reading. “It’s time to go to work. Gat, take your bag.”

Dalp’s walks with Gat to school were his favorite time with her. The walk from home to school was just long enough to let her pick a topic and let Dalp teach her a few things about it. The two left their home and walked up their street. The low sun warmed their faces and a cold breeze blew at their backs.

“So, what do you want to do when you grow up?”

She had answered this question differently every time he asked. She thought for a while. “This time I want to be an astronomer.”

“Ah. Good. There’s plenty of work that needs to be done in astronomy.”

“I’m going to find another planet.”

“I bet you are. How many have we already found?”

“Six, not counting World. But some astronomers are saying that there must be more, and when I grow up I want to help them find one.”

“They’ve had observatories on the dark side for many stars now. What makes you think they haven’t found all the planets?”

“All the ones they’ve found are farther from the sun than World is, so we can see them in the dark sky. So there could be planets closer to the sun that we would never see because they’re in the bright sky where the sun blocks out stars and planets. I read that an astronomer said that if there are no other planets closer to the sun, then by coincidence World is the closest, and scientists don’t believe in coincidences.”

“That’s right; they don’t. But how are you going to find a planet on the bright side of World? The sun will blind your telescope.”

“It’s not the sun, dad. It’s the sun scattering off the atmosphere. I just have to figure out how to get the telescope above the atmosphere, then the sun will still be there but the sky will be black, and I’ll be able to see the stars and I’ll be able to look for planets. I just don’t know how yet, maybe a giant tower on top of a mountain.”

“You’re right that the atmosphere is the problem, and I bet if you study hard and work on it with lots of other smart people, when you grow up, you’ll be able to figure something out.”

“When are you going to take us for a vacation to the dark side again? I haven’t seen the dark sky since I was eight.”

“I have a big project at work. It should be done in three or four moons. I’ll talk to your mom. Maybe we can spend some time on the dark side after that.”

moon

1. The only body that orbits World. It is best seen on the dark side, but is also the only body in the sky other than the sun that can sometimes be seen in the bright sky.They reached Gat’s school.

2. A unit of time equal to the time it takes for the moon to orbit around World. There are approximately 13 moons in a star.

“Bye, dad.”

“Learn a lot, my love.”

Dalp turned towards the center of town where he worked and quickened his pace. Animal-drawn wagons carried their loads down the street, and occasionally a noisy steam-powered wagon clanked by. The trees lining the sidewalk provided some shade from the fixed sun. Every one of their leaves was turned towards the glowing orb, and on the shaded side of every tree trunk moss grew. The cool wind that blew constantly from the dark side to the bright side had also bent every trunk slightly towards the sun.

What had been recently preoccupying Dalp was the rate of change of things, although he might have expressed it mathematically as the first derivative with respect to time. For a planet that was supposed to be more or less static, too many of its systems turned out to be very far from equilibrium. Water was the most obvious example. The planet’s water cycle was simple. Water evaporated on the bright side and made clouds. (Some people thought that near sunpoint the surface became so hot that water would boil, but this was speculation as no one had made any measurements any farther than sunangle +12 arcs and even those were very brief and at great danger to the scientists who ventured that far.) High hot winds blew the atmospheric moisture from the bright side to the ring, and there, depending on temperatures and where the clouds encountered mountains, some of the moisture returned to the surface as rain. This refilled lakes and increased river levels. But some of the clouds just kept going and ware pushed by the winds all the way to the dark side where they formed snow and hail. And some of the rivers in the ring ran towards the dark side and eventually ended as icy banks. And that was the mystery. That was where the system seemed to break. The ice on the dark side never melted. There was no liquid water on the dark side (except what was brought temporarily by people) but the solid water never rejoined the water cycle. It was a dead-end for water. It had been only a few generations ago, about a hundred stars, that measurements of lake and river levels began to be compiled and the horrible realization was made that these levels were slowly falling from star to star. One of the greatest technical achievements of the generation before Dalp’s was the diversion or damming of every single river that ran towards the dark side. In Dalp’s time, surface water was no longer allowed to leave the biosphere forever.

The terrifying challenge of Dalp’s generation was what happened after the dams and waterways were complete. It was generally assumed that water levels would reach some stable balance and remain there. Instead, water levels continued to fall, though slower than before. This was because hail and snow continued to fall on the dark side, leaving an open route for water to permanently leave the Ring. But clouds could not be dammed. This was so alarming that the data were kept secret. The implication was clear. At the current rate the Ring would run out of liquid water in about another two hundred stars and then all life in World would end. Dalp was one of the few people who knew, because he was one of the people assigned to find a solution. But even the problem didn’t make sense. The rate of change was all wrong. If World was billions of stars old, as all their scientists believed it was, how was it that it hadn’t run out of liquid water yet? Why hadn’t it all ended up as ice on the dark side? Why did the graphs show that they would run out of water two hundred stars from now, when by every calculation they should have run out before any people stood on World?

As he approached the center of town the buildings became taller. The multi-story buildings all had small windows on the bright side to illuminate each room without too much glare, and large windows on the dark side for scenery. His building was one of the more modern ones, and even had a steam-powered elevator. He reached his office building which housed several government departments including the Department of Water, for which Dalp worked. He took the stairs up to the sixth floor, preferring the quiet solitude of the climb to the noisy crowded elevator. On his way to his office he returned a few friendly greetings from colleagues and then closed his office door and sat at his desk.

He was responsible to review and implement a plan that would attempt to solve World’s secret water crisis. The plan involved establishing ice mines on the dark side which would excavate ice, melt it, and pipe the water back to the Ring. The water would initially be used for drinking and irrigation, but once enough mines were operational it would be poured into lakes and rivers to replenish liquid water for the entire biosphere. It was a plan of staggering magnitude that would likely take a generation to reach full capacity. If the first mine was a success, hundreds would eventually be built, but the definition of success was still being strongly debated. How much water output could be expected from each mine? How many accidental deaths and injuries could be tolerated? The mines would involve the first continuously occupied habitations on the dark side, which in itself was risky. Part of his task was to choose the site for the first mine. The ideal site would have an enormous field of deep ice uninterrupted by rock or other debris and would be close enough to the ring to minimize the length of the pipeline carrying the water back and to minimize the distance that supplies and messages would need to travel. After he approved a site construction would begin on the pipeline and the dwellings, and small teams of workers would move in permanently.

Dalp spread out several maps on his desk. The Ring had already been entirely explored and mapped generations ago. The bright side had been explored to sunangle of about +10 arcs and decent maps of that region had been made. Though expeditions into the dark side had reached farther, maps of the dark side were much less accurate and much more incomplete. The reason was simple. The bright side had great visibility and surveyors could make measurements of geologic features as far as they could see. The dark side could only be lit by firelight. Even when surveyors brought large wood-burning lamps with curved reflectors to slice through the darkness, their visibility was frequently hampered by snow and hail.

There was a knock at the door and one of his coworkers bounded in.

“Hey Dalp!”

“Give me some good news, Fras.”

Fras had joined the department about ten stars after Dalp. Dalp quickly found him to be the brightest engineer of Dalp’s subordinates and the one he trusted most.

“Good news? Well, we’re not all dead yet. By the way, how’s Gat doing?”

“She’s brilliant and pretty.”

“Hmm. Must take after her mother. You still haven’t talked her out of going into engineering and wasting her life at a desk like us?”

“You love engineering! What else would you rather be doing? Don’t answer that. Did you come in here to plan my daughter’s life or to give me an update on the project?”

“OK, Dalp. I actually do have some good news. The first two boiler prototypes are operational.”

Fras was in charge of a segment of the project that was to produce the two things that the mines would need in large supplies – heat and mechanical power. About a generation ago steam power had been developed and replaced animal muscle power as the best way to push cargo, lift loads, and power farm equipment. Steam power required wood for fuel and water to generate steam but was still much more efficient than using work animals, which also required fuel and water. Wood fires were also used to provide heat and light, both essential for working on the dark side. The use of solar power was largely limited to roof-top water heaters for homes in the Ring. Fras’s contribution, which was intended to be a minor part of an ice reclamation project, would eventually revolutionize power production on World. He designed and implemented boilers.

Boilers were simply metallic containers that used sunlight to heat water into steam. They were large flat squares which were designed to cover as much ground, and thereby catch as much light, as possible. They covered about as much ground as a family home. Boilers were very short (their top surface was about at knee level) so that their entire volume could be heated by their top surface. The top was painted black to reflect as little sunlight as possible, and around the boiler mirrors were placed to direct more light at it. In one corner was an intake valve through which low pressure water would continuously pour. In the opposite corner was an outlet valve, through which, if the boiler reached an adequate temperature, high pressure steam would leave. The concept was simple. Boilers would be driven out and left on the bright side. A compromise was made in calculating their optimal distance from the Ring. The farther they were placed from the ring, the more light each could collect and theoretically the higher pressure and temperature output each could achieve, but this would also require longer water and steam pipelines and farther more dangerous maintenance trips. The steam pipelines were insulated so that the steam did not lose heat and condense into water on the way back to the ring. The result that Fras imagined was a cheap and endless supply of high pressure steam that they could use to warm heaters on the dark side and operate machinery. The goal was to avoid burning wood for heat or for mechanical energy and save wood fires for production of the one commodity they had no other way of creating – light. The only exception to this was for mobile machinery such as steam powered wagons. They would still need to be wood-fueled since they could not be attached to a stationary steam pipe.

“I didn’t even know the second boiler had been placed on the bright side yet.”

“That’s because you spend all of your time with your nose in those maps. You need to get out more. The second one is placed and both of them are working.”

“And what kind of data are you getting?”

“The temperature and pressure outputs are consistently meeting what we were expecting.” Fras said, letting a very satisfied grin settle on his face.

“That’s great! Congratulations.”

“It is a beautiful thing, if you don’t mind me praising my own work.”

“If I did mind, would you stop?”

“No. By the way, I think they can probably handle having the water input flow rates a little higher than what we planned. We’re testing that now. Oh, and after checking the steam output from both boilers by instruments and collecting enough data to fill your office, we got bored and wanted to do a more practical demonstration.”

“Are you about to tell me something bad?”

“No. I’m about to tell you something good. We went to the people at Facilities Division who maintain this building and asked them to let us connect the steam pipe here and to turn off the building’s furnace.”

“You’re kidding.”

“No. It took some friendly arm twisting, but they agreed, and it’s been working fine and all the people who work in the building don’t even know about it.”

“You’re saying that all the hot water in the building is being heated by your boilers out on the bright side?”

“Yes. The building isn’t burning a single scrap of wood. But not just that. We’re powering the elevator.” His grin got distinctively broader.

Dalp’s eyes widened. “You’re getting enough energy to power the elevator and heat all the water in this building out of two boilers?”

“More than enough. We’re venting excess steam right now and wasting it because the pipes to the dark side are still under construction and we can’t think of anything else useful to do with it. We thought about venting it through a giant air horn just to make some noise, but we thought it might scare people.”

“Good judgment. I’m glad you didn’t do that.”

“It was my idea. I had to be talked out of it.”

“I’m sure. I should have taken the elevator when I came in. How was the ride up?”

“Just like any other time. The other passengers were just as bored as they could be. They had no way of knowing that the worker who normally works in the basement shoveling wood into the furnace was ‘promoted’ to planting a garden out front, or that the energy that brought them from ground level to their office was generated far away in a box hot enough to burn a steak on. You realize what this means, don’t you?”

“That I should take the elevator on my way home?”

“We could have a hundred boilers operational in the next star, more if I can get the goons at manufacturing to streamline a few processes. This can be much bigger than supplying the dark side ice mines with heat and power. Eventually, this can supply everybody with heat and power.”

Dalp sat and absorbed what he had heard.

“One other thing,” Fras continued. “I don’t want to put too fine a point on this, but while I was designing and testing the boilers, you were supposed to choose the location of the first ice reclamation site.”

“You’re saying that you finished your job and I haven’t finished mine.”

“Yes, but in a nice way. You’ve been staring at those maps for half a moon. Dalp, the maps are incomplete, and given the terribly difficult conditions under which they were made I wouldn’t be surprised if they were also wrong in some places. You’re not going to get any more information out of the maps.”

“You’re right. Of course you’re right. I just have to make a decision with the little information I have.”

“Not necessarily.”

“What do you mean?”

“You’re looking for a spot on the dark side that has just a few important criteria,” Fras said, counting each item on his fingers. “You need a huge contiguous volume of surface ice that’s relatively free of rock or other debris. It should be close to another place where the ground is covered with little or no ice to provide a stable platform for the permanent buildings. It should be as close as possible to the Ring to minimize pipeline length and travel time. And, finally, steam wagons have to be able to drive between the Ring and the location, so there has to be at least one path connecting the two with fairly gentle terrain.”

“Yeah, but this isn’t engineering school. Restating the problem for me doesn’t help that much.”

“I’m just saying that you’ll never get that much detailed information from your maps, but each of those criteria would be obvious if you saw the area. I’m saying you need to use the maps to pick a general area and take a trip to the dark side and pick a good site with your own eyes. Like I said, you need to get out more.”

All expeditions to the bright side or the dark side were risky, and no one ever went alone.

“Are you saying you want to go with me?”

“Yes. The boiler project is running itself for the short term. My team can manage without me for a while.”

“What phase of the moon are we in?”

Expeditions to the dark side usually were scheduled during full moons to make the most of natural illumination.

“Just past the full moon. If we don’t go soon, we’ll have to wait for the next full moon.”

“I’ll have to requisition a wagon, and dark side gear. That’ll take a little while.”

“Yes. That’s why you’re the boss.”

Fras left. Dalp spent the rest of his time at work getting Fras’s plan approved by various department heads, making a supply list, making sure a wagon was available, and choosing a broad area that they would explore. When all was ready, he informed Fras, and went home. He took the elevator on the way down.

On his walk home, his mind raced. He kept thinking about various possibilities. The best case scenario was that they find an enormous ice field, build a functioning mine, and within a star or two start reclaiming enough water to stabilize reservoir levels. Then, when the danger had passed, they could make the project public and assure everyone that the future of the water supply was secure. The worst case scenario was that on the icy terrain in the pitch dark he and Fras would drive their wagon over a cliff and would never be heard of again, and the next expedition would have to start from scratch.

Dalp arrived home. While he ate he told his wife about his impending trip. Gat was already sleeping in her room.

“How dangerous is this going to be?”

“Not any more dangerous than any other trip to the dark side. We’ll have a well supplied wagon, and others have gone farther than we’re going. If anything goes wrong, we’ll turn around and come back.”

She looked at him quietly. She didn’t have to list the dangers involved in even the best planned trip. Their ability to stay warm, have light, and keep their steam-powered wagon moving depended entirely on their supply of wood staying dry. Wagons were fairly reliable, but if theirs broke down far from the Ring, they’d never survive the hike back. And, of course, there was no way to call for help or send a message to anyone else. Plenty of explorers died on well planned trips away from the Ring.

“Be careful.”

“I promise I will.”

They spent the rest of their time together quietly until they heard the rumbling of a large wagon approaching on their street. Dalp kissed his wife and walked outside. He saw Fras driving the wagon and waving at him. Dalp climbed in, and they drove off.

Steam wagons built for missions to the dark side were larger than ones for general use. They had to keep their cargo enclosed to protect it from likely rain or hail, especially the wood they would need to feed the wagon’s furnace, and the passenger cabin had to be insulated. The furnace had small adjustable vents that opened on the inside of the wagon to keep the interior warm, and an inside window to illuminate the passenger area. The front of the wagon also had a lensed window from the furnace to the outside which illuminated the wagon’s path.

As they drove out of the Ring, the sunlight slowly dimmed and they felt noticeably colder.

“The cold weather gear is right behind your seat.” Fras said. “You might as well change now.”

Fras was already wearing his multi-layered insulated overalls, and Dalp changed into his. They opened the vents from the furnace slightly to get some more warmth. Dalp fed the furnace while Fras drove. Soon the sky was dark, revealing stars and a large moon. A rim of sunlight remained in the sky far behind them. Their path was lit only by moonlight and by their furnace, and they slowed as they picked a careful trail into the dark.

“We might as well take turns getting some sleep.” Fras suggested. “Why don’t you try to sleep for a while? I can keep driving. I’ll wake you up if you need to feed the furnace.”

“That sounds good, thanks.” Dalp turned his face away from the furnace window and closed his eyes. He found the constant rattle of the engine soothing. His thoughts wandered. He thought how odd it was that people (and animals, for that matter) liked to sleep in the dark. No wonder that he got sleepy as soon as they left the Ring behind. Bedrooms were built on the dark side of houses for that reason, and animals would find shade behind some large object when they felt sleepy. For practical reasons, most families slept at the same time, but different cultures had different traditions about sleep time. In some places the entire town had commonly accepted times when everyone would sleep; in other places each household had its own schedule. He remembered that recently some botanists found that many trees reacted strangely to the dark. It was long known that many plants can sense light, since they bent their leaves and branches toward the sun. So scientists took some trees and transplanted them in an area that was shaded by a large hill. Normally, of course, no plants would grow in the shade. They expected that the trees would just die, but they were curious if the leaves would still all point in the same direction. What happened was very peculiar. The leaves turned different colors: first yellow, then red, then brown. Then the leaves all fell off. They thought the trees were dead at this point, but the limbs didn’t decay or weaken. They then took some of the trees and transplanted them back to their original bright space. The trees grew new leaves! This meant that trees had adapted to deal with periods of darkness, which, of course, made no sense…

“Wake up, boss”

Dalp opened his eyes. Outside was now lit only by moonlight, except for the thin beam of light extending forward from their wagon. He blinked the sleep from his eyes. He noticed he was hungry, and guessed that he had slept quite a while.

“Thanks for letting me sleep, Fras. How are we doing?”

“Fortunately, no rain or hail yet. We’re almost at the first general area you wanted to look at. You should eat something, and then I’d love it if you drove for a while.”

“Sounds good.”

He reached behind him and dug through the supplies and grabbed some food. While he ate, he looked ahead at the terrain. They were driving up a large ridge of hills over ground that was a mixture of rock and ice. Fras was slowly picking a route that would get them over the ridge without going over any areas too steep for the wagon. He had a map and a star chart open on his lap.

“The first area we’re looking for is just over this ridge. We should be able to get a good view of it from the top.”

“Great work, Fras. I can take over now, if you want.” He swallowed his last bite and took a long drink from the large water bottle. Fras stopped the wagon and they traded seats. Dalp drove on uphill while Fras started eating.

Soon they reached the crest of the ridge. Before starting down the other side, Dalp stopped the wagon and looked out the window at the land before him. The ridge of hills that they had climbed tumbled down into what must have been a very large valley or basin that had filled with ice. The entire view past the hills was a flat uninterrupted sheet of ice as far as they could see. Dalp turned to Fras to get his attention but saw that Fras was already staring out the window.

“I’d say you’ve found your first site, boss” said Fras. He was so astonished by the endless sheen of ice that for a moment he forgot to chew his food.

“I think you’re right, Dalp. This may be a good second and third site too.”

“I don’t want to get too excited at first glance, but I wasn’t expecting anything nearly this good.”

“Let’s get a closer look” Dalp said and started the wagon forward. “There could still be some problems. The ice layer could be very thin, or full of rocks, but it sure doesn’t look like it from up here.”

They drove down the hills, Dalp trying to choose a careful path down but frequently staring away at the flat, reflective, and apparently endless ice that lay far beneath them. He zigzagged the wagon slowly down each slope, with each turn sweeping the wagon’s light beam over the shimmering ice.

“Hey!” Fras’s exclamation was so sudden and loud that Dalp almost yelled in surprise. “Look there!” Fras pointed out the window about half of the way between them and the horizon.

“Where? I don’t see anything.” Dalp strained his eyes in the direction of Fras’s finger but saw only the flat ice that stretched out of sight.

“Our light beam just crossed over something way out on the ice. Now the beam is just to the right of it. Back the wagon up a little to get the light beam over there.” He flicked his finger slightly to the left.

Dalp slowly maneuvered the wagon back and to the left while Fras shuttered the interior furnace window, darkening the inside of the wagon so their eyes could see better in the dark. As the oval of light swept slowly to the left, it illuminated very obvious but distant irregularities protruding from the ice. Dalp stopped the wagon and they both squinted into the distance. What they saw was a crop of clearly geometric structures extending straight up out of the ice. Fras reached for his notebook and began sketching the scene.

“Those, um, look like, uh…” Dalp stammered.

“The tops of buildings” Fras finished Dalp’s thought.

“Is that what you’re seeing, too?”

“Yeah. It looks like about eight of them, fairly close to each other.”

“But no one’s ever built permanent structures this far from the Ring.”

“You mean except for those.” Fras looked at the sky and at his star chart and calculated their present location, which he recorded.

“Let me guess.” Dalp ventured. “You’d like to drive out there to take a look.”

“Actually, I’m thinking that we have no idea how thick or stable the ice is, and the buildings are really far, and it’s not part of our mission plan to discover or describe the very first known buildings on the dark side, and if we get killed on the way there no one will find out about them.”

“This might be the most important archeological find ever.”

“Except for the ‘might’ part. But we’re not archeologists. The buildings might not even be stable themselves, and we have no idea how old they are. Once they have an operational ice mine here with a permanent team of workers and steady supply deliveries, they can send out a team of archeologists to survey the site and start excavating. We wouldn’t even know what to look for.”

“Since when did you become the thoughtful restrained one?”

“I just think I’d like to die some place warmer.”

“Sounds good. Let me know when you’re done drawing and then I’ll keep heading down the hill. I wonder how tall the buildings are. The ice might be covering more than half of them.”

“I wonder why anyone would build buildings on the dark side.” Fras said, continuing to stare at the distant buildings while scratching at his notebook.

“Could it be that the Ring has slowly changed locations over time? The Ring hasn’t moved as long as we’ve been keeping records, but that’s only several generations.”

“But look at the shapes of these buildings. Some of the roofs look like perfect squares. Most of them look like they have several stories sticking above the ice, and, for all we know, a bunch below. These aren’t primitive brick or mud. The amount of ice surrounding them suggests that they were built a long time ago, but if they were built a long time ago, they should be more primitive.”

“You think there could have been people who had artificial light and heating and decided to build a city on the dark side?”

“Why bother when you can live on the Ring?”

“Maybe they were banished here.”

“But if they had artificial light and heat then they were more advanced than we are now. What happened to them? Why don’t we have records or even legends of buildings on the dark side? Oh, well. I’m done drawing. The rest of the mystery will be for the archeologists to sort out. I’ll be content with the eternal fame of being on the expedition that first discovered whatever the heck they turn out to be.”

“I’m glad you have reasonable expectations.” Dalp said, starting the wagon forward and returning the distant crop of buildings to darkness.

They finished driving down the ridge, and Dalp stopped the wagon when it neared the ice table. Immediately below them, the rocky hills gave way to the flat endless expanse of ice. They climbed out of the wagon, bracing themselves against the cold. They needed only to collect a few ice samples and drill a few holes in the ice to attempt to measure its depth. Then they could go back home and report the recommended location of their first ice mine. They worked quickly, sawing through the ice, and putting large ice blocks in waterproof bags in the wagon. The blocks would later be melted to measure the amount of debris in it.

“If you’re getting too cold, take a break in the wagon” suggested Dalp.

“I’ll make it. Besides we’re almost done. I’m looking forward to getting out of here and seeing the sun again.”

They finished stowing their samples and recording their measurements. They left a tall reflective marker to make the site easier to find by the next expedition. They climbed back inside the wagon and opened the furnace vents fully to defrost their hands and feet. Dalp started the wagon and turned it to go back up the hill they had descended.

“I think we did well, Fras.”

“I agree. It’s an ideal site. That’s a whole lot of ice, which will make for a whole lot of drinking and farming water.”

“I can’t stop thinking about the buildings we saw.”

“How tall do you think they are? None of the holes we drilled hit rock, so we have no idea how deep the ice is. We just know it’s deeper than our longest drill bit. Those buildings could be huge. Nine tenths of their height could be under the ice.”

“You’re right. We won’t know until the site is excavated. It’ll take a long time just to build the residences for the people who will need to work here. No one will be able to tell us much about those buildings for a long time.” Dalp spoke while trying to retrace their zigzagging path up the ridge.

They both saw it simultaneously after a sharp right turn. They had probably just missed it on the way down the hill, but on the way back it was obvious. Dalp slammed the wagon to a halt, nearly sending Fras into the front window. They both exclaimed inarticulately.

Fras grabbed his notebook and started drawing. “What in World is that?”

“It’s a sign.”

“Well, obviously it’s a sign! I don’t know if I should be more terrified by how big it is, or by the fact that I can read the letters. Do you realize how strange it is that the people who did this used the same alphabet we do?”

“What does the word mean?”

“Hollywood? I have no idea.”